Cryptography 101 for Blockchain Developers (Part 1)

This article is meant for blockchain developers who want to start learning math and cryptography, but the concepts explored are strictly mathematical.

A brief overview of the article

This article is my first ever math-focused piece of writing. The topics covered will follow the Cryptography 101 videos from Openzeppelin's Youtube channel. I have watched each of the videos a few times now and also referred to some external resources to plug conceptual gaps as and how I saw them.

This is my own, original interpretation of the concepts, but credits are obviously due to KoalateeCtrl for publishing such awesome and easy-to-understand videos.

This article assumes that you are familiar with modular arithmetic concepts like modular addition and multiplication. If you're ready, let's dive right into it!

Groups

But if you have no idea what a group is in the mathematical context, this is the place to start reading from.

Group theory is the mathematical study of groups. Simply put, a group is defined by two items:

a set of elements, such as {0,1,2} or {0,3,5,7},

and an operation, most commonly, but not exclusively addition(+) or multiplication(x).

A set of elements(E) under an operation(O) needs to fulfill four basic mathematical properties to be considered a group(G).

Closure: This means that using the operation of any two elements in the group results in an element that is also in the group. In other words:

For any \((a,b) \in G\), \((a.b)\in G\)

Associativity: For any three elements in the group (a, b, c), the operation of a and b first, and then c, is equivalent to performing the operation of b and c first, and then a.

In other words:

For \(a,b,c\) in group \(G\), \((a.b).c = a.(b.c)\)Identity: There is a special element in the group (let's call it "I") such that the operation of any element a in the group with 'I' results in a.

In other words:

One element \(I,a\) \(\in G\) such that \(I.a = a\)Invertibility: Every element a in the group has another element b in the group, such that the operation of a and b gives us the identity element I.

In other words:

For any \(a \in G,\) there exists a \(b \in G\), such that \(a.b = I\)

Just to be clear, the rest of the elements do have to satisfy the property.

So just to recap: a Group is a set of elements and an operation that fulfill the four properties of closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility.

Now some groups also satisfy a fifth property, called commutativity. To satisfy this property the order of elements upon which an operation is being performed does not matter. In other words:

For any \(a,b \in G\), \(a.b = b.a\)

If a group has this fifth property in addition to the previous ones, it is referred to as an Abelian group or a commutative group.

Example

Consider a group as follows:

The set of elements is made of positive integers mod 6. So, {0,1,2,3,4,5}.

The operation is modular addition with mod 6.

You can check if the closure property holds.

Is (1+2) % 6 part of the group? Yes.

Is (3+5) % 6 part of the group? Yes.

You can verify that the closure property will hold for any two elements from the set. Hence, the closure property holds.

You can similarly verify that the 3 other properties also hold.

Hence, this set of elements contained under an operation of modulo addition 6 is a valid group.

The Identity element for this group is 0.

You can read on if you are not able to figure out the answer.

Fields

Having understood what a group is, let's proceed to another important concept - a field. A field is a set of elements that:

form an Abelian group under both addition and multiplication operations,

and they adhere to the distributive property.

The distributive property is fundamental to defining fields. It's important to note that the distributive property relates to two operations, usually referred to as addition (+) and multiplication (*), which are used on the elements of a field.

Here's how the distributive property is formally defined: For all elements a, b, and c in a field,

Left Distributivity: a (b + c) = (a b) + (a * c)

Right Distributivity: (b + c) a = (b a) + (c * a)

Think about the previous set of elements again. The set of positive integers mod 6.

Even though that set of elements forms an abelian group under addition, it DOES NOT form an abelian group under multiplication. In fact, it does not form a group at all under multiplication.

The set of integers mod 5 does form a field though.

Do you know what else forms a field?

A set of all Real Numbers!

You have been using this field without realizing that it was one. How cool is that!

Do remember though, that a set of all real numbers forms an infinite field, not a finite field.

Note 📝: Real numbers include numbers like \(\pi\), -2.9, 47, etc..

Please note that \(\pi\) is an irrational number, but is still a real number.

Elliptic Curve Groups

Now that you understand groups and fields, you are ready to look into Elliptic curve groups. Please keep the previously discussed concepts in the back of your head, they will come in handy.

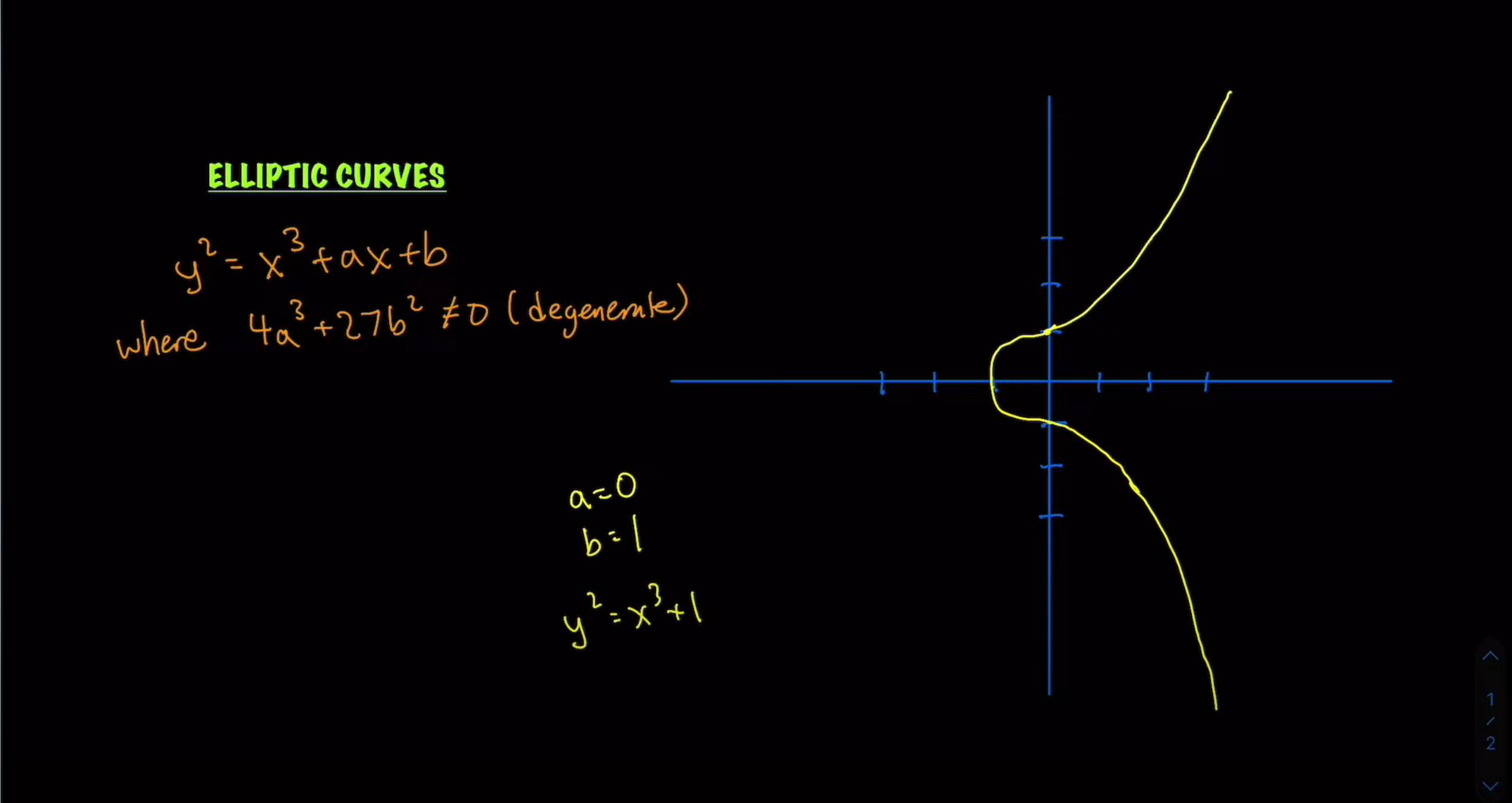

Now, a very simple but precise definition of an elliptic curve will look like this:

An elliptic curve is the set of points that lie on the equation \(Y^2 = X^3 + aX + b\), where \(4a^3 + 27b^2 \neq 0\).

Note 📝: The condition \(4a^3 + 27b^2 \neq 0\) is essential to ensure that the elliptic curve defined by the equation \(Y^2 = X^3 + aX + b\) doesn't have any singular points - that is, points where the curve isn't smooth, but instead intersects with itself.

This is what an elliptic curve looks like for arbitrary values of a and b:

You probably realize that the curve extends into infinity and the field of points that satisfy the curve will be the infinite field of real numbers.

But in the context of cryptography, we want to limit the field of numbers we are dealing with. So let us try limiting the scope of our elliptic curve.

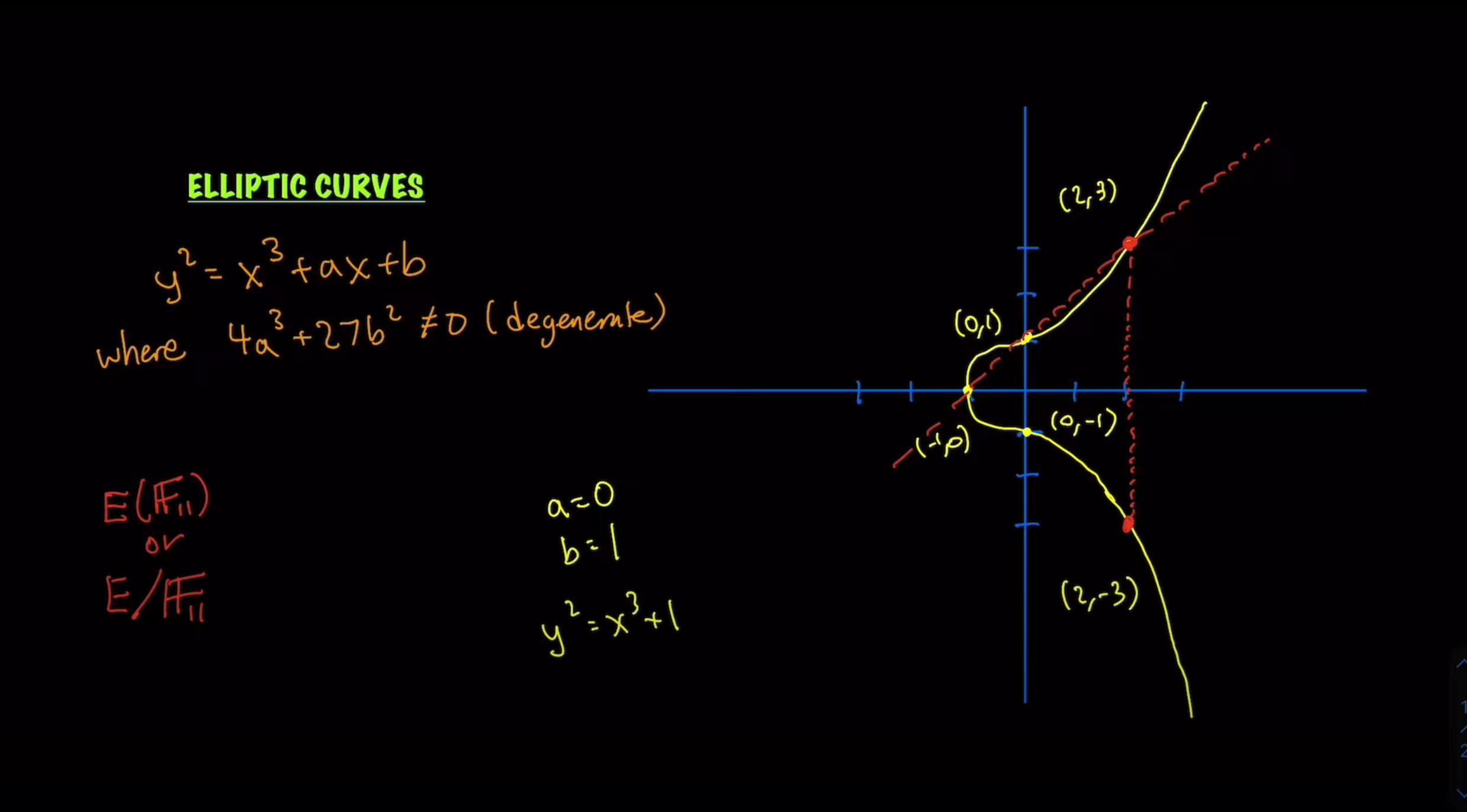

- First, we limit the field of values to integers. So any point on the curve where either X or Y are not integers, is no longer a valid point. Therefore, points like \((3, \sqrt[2]{28})\) are no longer valid but points like \((2,-3)\) still count.

Now let us further limit the field of integers to be a field of integers modulo 11. This means that any coordinates where \(X \text{ or } Y > 11\) are no longer valid. This limits our field significantly. Can you name all the valid points here?

They are \([{(-1,0), (0,\pm1), (2,\pm3),(5,\pm4),(7,\pm5),(9,\pm2)}]\).

Important note 📝: Please note that the calculation is to be performed for integers in the field modulo 11.

So while (5,4) does not satisfy the equation of the curve in a generic manner, the calculation right now looks like this:$$(4^2)\text{%11} = (5^3 + 1)\text{%11}$$

So what do we have now?

In proper mathematic jargon, we can say that:

We now have the elliptic curve \(Y^2 = X^3 + b\) defined over the finite field of integers mod 11.

That was a mouthful, but take a moment and you should understand what that statement says. Essentially we have the same elliptic curve as before but it is now defined over a different field, a finite field.

This is how the equivalent mathematical notation will look like.

\(E(F_{11}) : y^2 \equiv x^3 + 1 \pmod{11}\)

Hopefully, this isn't scary now that you understand the complicated jargon.

Some ways to find solutions for our Elliptic curve

I brute force my way to find some valid solutions for our elliptic curve bound by the constraints, but there should be a valid way, right?

Consider this:

Straight line method:

\((-1,0) \text{ and } (0,1)\) are obvious solutions. Now, a straight line that passes through the straight points can be represented by \(Y = X +1\).

If we equate this to the equation of the Elliptic curve, we get a solution for \(X = 2\). Hence, we just found another point that lies on the curve. Now, since elliptic curves are symmetrical along the X-axis, by finding one value of \(X\), we can find two coordinates for two values of \(Y\).This diagram should clear things up:

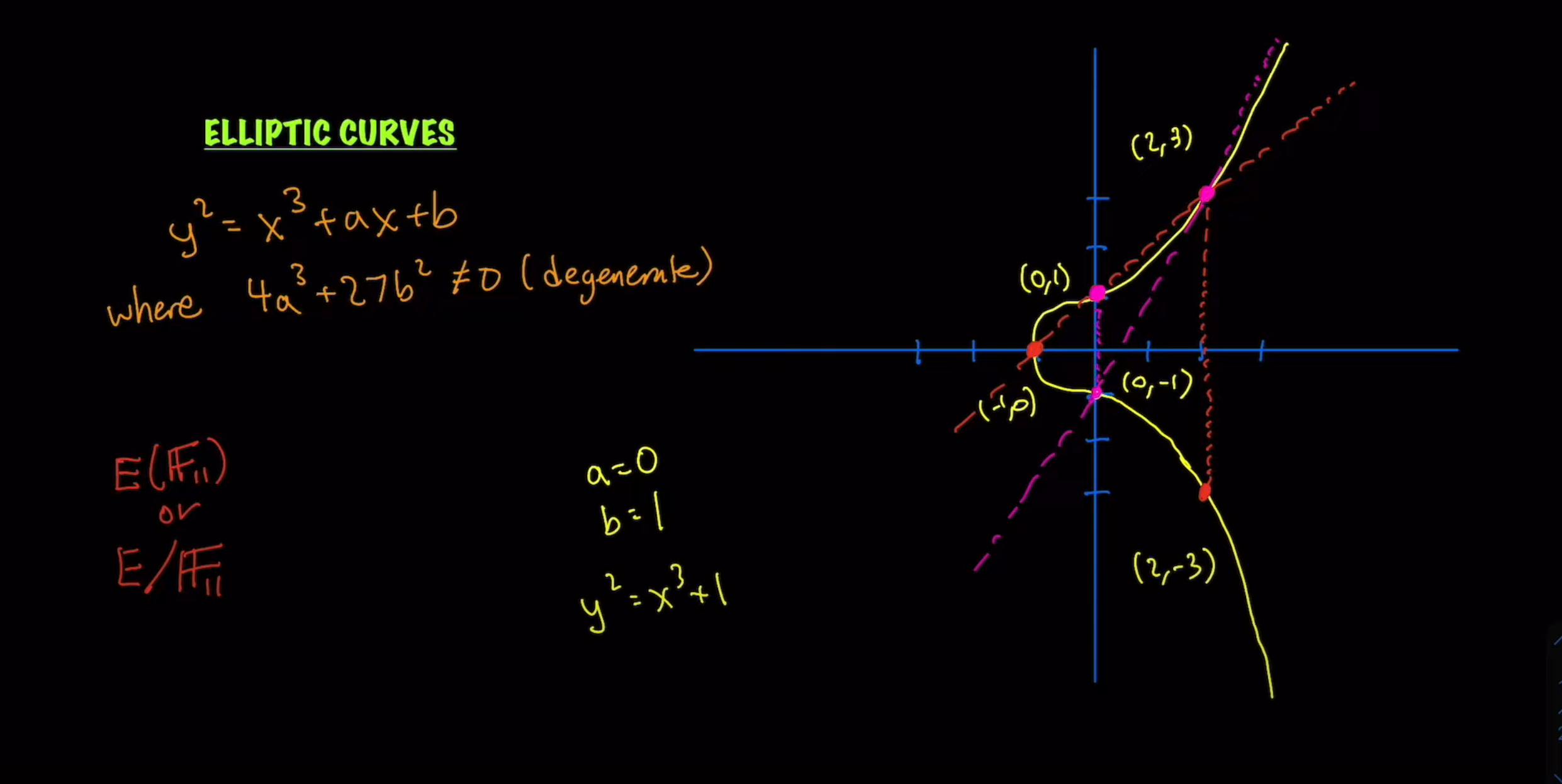

Tangent Method:

Consider the point \((2,3)\) which we know is a valid point on the curve. A tangent to the curve at the point \((2,3)\) will give us the equation for another straight line. And that straight line will intersect the curve at \((0,-1)\). And the mirror image of that point is \((0,1)\), another valid point.

Again, this picture should clear things up:

Let us summarize what we did till now.

We started with the definition of an elliptic curve and showed what it looks like.

We then said we don't want to work over an infinite field such as the real numbers so instead we Define this elliptic curve over a finite field.

Then we looked at two different methods to find valid points on an elliptic curve defined over a finite field assuming we already know one or two other valid points.

The first method was to connect two existing points on the Curve and where it intersected the curve a third time was another valid point.

The second method was the tangent method. If we draw a tangent line to a valid point where it intersects the curve a second time is another valid point.

For both these scenarios we could take that newly found valid point and flip it over the x-axis to get another valid point.

So how do groups tie into our Elliptic curve investigations?

Recall that a Group(G) consists of a set of elements and an operation. The element-operation combination has to satisfy the 4 properties of closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility.

Let us turn what we have into a group.

What will be the set of elements that form our group?

That's easy. Those will be the set of coordinates that satisfy the curve within the defined field. Each valid coordinate will represent an element of the group.

What will be the operation that forms our group?

The defining operation for our group will be Elliptic curve addition. Let us look at how it works:

Point Addition (P + Q = R): This refers to adding two distinct points P and Q on the curve to get a third point R. The process is as follows:

Draw a line through points P and Q.

This line will intersect the curve at exactly one more point, say 'R'

Then reflect 'R' over the x-axis to get '-R'. This is because elliptic curves are symmetrical about the x-axis.

So, the "sum" of points P and Q is this third point R.

Point Doubling (P + P = R): This refers to adding a point to itself. The process is different than point addition:

Draw a tangent line at point P.

This tangent line will intersect the curve at exactly one more point, say 'R'.

Then, as in point addition, reflect 'R' over the x-axis to get '-R'.

Therefore, the "sum" of point P and itself is this third point R.

An important thing to note is that this addition operation on elliptic curves forms an Abelian group.

This group structure is fundamental to the applications of elliptic curves in cryptography.

The identity element in our group will be point \(O\) at infinity. This point cannot be denoted on a graph but will help in satisfying the properties of an Abelian group.

Conclusion

This article was a handful. Took me a long time to understand and write down everything.

We are however not done. I will go through some more concepts covered in Openzeppelin's cryptography videos in part 2.

If you liked this article, I would appreciate a like and follow.