Cryptography 101 for Blockchain Developers (Part 2)

This article is meant for blockchain developers who want to start learning math and cryptography and is the second and last part of this series.

Prerequisites

This article is the second(and final) part of my Cryptography 101 articles. You can check out the first part at this link.

I will presume knowledge of all the concepts I discussed in the first article, while writing this article.

Again, the credit for the original content goes to KoalateeCtrl.

Generators

To go through this concept, let us first take a break from Elliptic curve groups, and bring up the first group we looked at:

The group of additive integers mod 6.

The elements of this group are \({[0,1,2,3,4,5]}\).

A generator of a group is an element that is in the group such that if you apply the group operation to this element over and over and over again, you end up getting every single element in the group.

Let us take the element \(1\) for example, let us call it \(G\).

Therefore,

\(G=1\)

\(2G = G + G = 2G = 2\)

Similarly,

\(3G=3, 4G=4, 5G=5, \text{ but } 6G=0\)

You can clearly see that we could generate the whole group by continuously iterating the element G through the additive modulo operation.

Therefore, we can say that:

\(1\) generates the group of integers mod 6 under addition

In other words, 1 is a generator of this group.

Generators are useful because now any element of the group can be represented as a scalar times a Generator \(G\).

For example, we can rewrite the previous group as:

\(G = {[0,1,2,3,4,5] = [6G,G,2G,3G,4G,5G]}, \text{where } G=1\)

Now that this makes sense let's go back to our example of an elliptic curve. group.

More precisely, the elliptic curve \(Y^2 = X^3 + 1\), defined over the finite field of the integers mod 11.

If you take point \((7,5)\) and perform point addition on this point repeatedly, you will see that you can generate all the elements of this group. Hence, the point \((7,5)\) is a generator\((G)\) of this group.

The order of this group, in other words, the number of elements in this group, is 12.

Discrete Logarithm problem

We discussed so much mathematical theory. Why though?

What can we do with Elliptic curves, that makes it worthwhile to study them?

Think about what we just fond out:

We can add any two points \(P\) and \(Q\), and the result stays within the group.

We also know that we can do \(P + P\), and the result stays within the group. In fact, we can find out \(nP\), for any \(n \in N (Natural Number)\).

In other words, we can perform scalar multiplication on a point.

The whole point of doing this was to take advantage of the hardness of the discrete log problem, specifically for elliptic curve groups. Let us see how that works.

Let us say I am a person \(A\) with a point \(P\). I also have a scalar \(a\).

We know we can find out a point \(S= aP\).

Let us say \(a=1029\). how do we find \(S\)?

Well, we can perform point doubling on \(P\) to get \(2P\).

We repeat the process to get \(4P\). And again to get \(8P\).

So on and so forth till we get \(1024P.\)

After that, we can break down \(S = 1024P + 4P + P\).

We can do that because we already know the values of \(P\) and \(2P\).

As you can see, this is a problem of \(logn\) complexity because we can double our results every time. Thus, even if \(a\) is huge, \(S\) will still be something we can calculate.

But what if we already know \(S\), and \(a\) is what we want to find out? Think about what that means for a minute.

Now we will have to add \(P\) to \(P \) \(a\) number of times till we get back \(S.\) Keep in mind we are NOT point doubling here. We need to individually add \(P + P + P + P........ \) so on and so forth till we get \(S\).

But what if \(a\) is a large scalar number? And by large, I mean laaaaaaaarge!

Like 300 digits large.

Suddenly it becomes unviable to find out \(a\) from \(S\), but we can still find out \(S\) from \(a\).

This is known as the discrete logarithm problem in Elliptic curves.

Given a point \(S\) equals \(a\) times \(P\), it is "easy" to calculate \(S\) if we know \(a\), but it is extremely hard for someone when you only give them \(P\) and \(S\) to find the secret value \(a\). This is exactly the reason why we use elliptic curve groups in cryptography.

We can make up an infinite number of elliptic curves by tweaking the values of \(a\) and \(b\), in the equation \(Y^2 = X^3 + aX + b\).

Recap till now

This picture illustrated what we learned till now:

Also, let us review elliptic curve groups:

In an elliptic curve group, the elements are elliptic curve points. The group operation is addition, and we can add different elliptic curve points together to get another elliptic curve point in this group.

We can also multiply a scalar with an elliptic curve point because that's just the same as adding a point to itself that many times.

For example, \(4P = P +P+P+P\).What we are unable to do is multiply two elliptic curve points together.

The number of elements in this group is called the order of the group.

Every group has at least one generator usually denoted as \(G\), and is an element that if you apply the group operation to this element over and over and over again, you end up getting every element in the group.

Elliptic curve pairings

Let us understand homomorphism before moving on to Elliptic curve pairings.

Consider three points:

\(A = 200G\)

\(B = 275G\)

\(C= 475G\)

We know that:

We can calculate \(475G\) independently of \(A \) and \(B\), if we know the value of \(G\).

We can also get back the value of \(C\), by adding \(A\) and \(B\), since we can add any two points in an Elliptic curve group.

Thus, Elliptic curve groups are said to be holomorphic under addition.

Now let us turn this around.

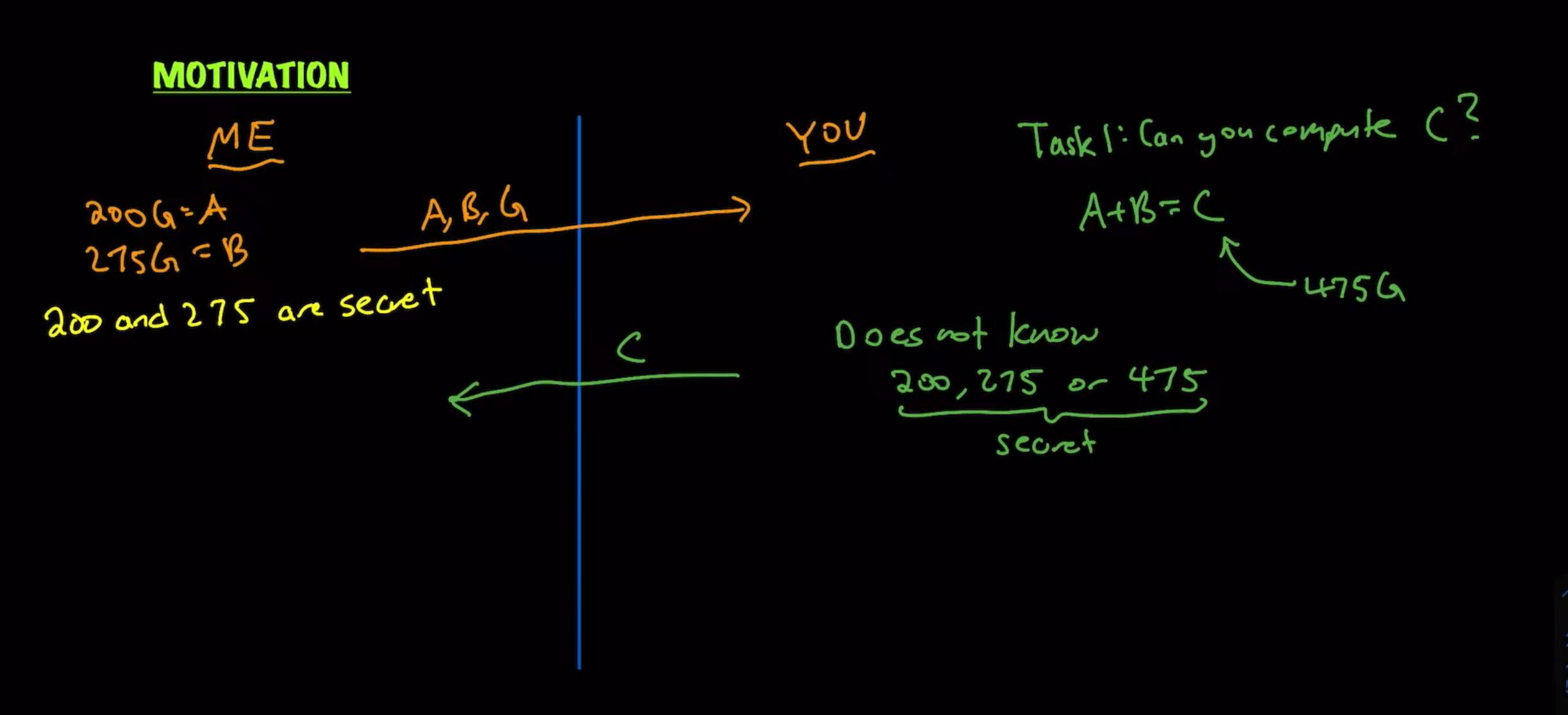

Say I made \(A\) by doing 200 times \(G\) on my own, and I also made \(B\) by doing 275 times \(G\) on my own.

I only give you \(G, A\), and \(B\), and I never tell you the secret values of 200 and 275.

Now it becomes really difficult to find out the values of 200 and 275.

Now you, as the counterparty can still compute \(C = A+B\), (provided you know \(A\) and \(B\)), but you won't know the scalar values they have been multiplied with.

Thus, you can check my work without knowing the underlying secrets.

Now let us start talking about what an Elliptic curve pairing is.

(\(e\)) is a mapping that takes elements from two groups, \(G_{0} \text{ and } G_{1}\), and returns an element from the target group \(G_{T}\).

Note that \(G_{0} \text{ and } G_{1}\) are both Elliptic curve groups. If they are the same group, \(e\) is called a symmetric pairing, otherwise, it is called an asymmetric pairing.

\(G_{T}\) on the other hand is not an Elliptic curve group. Although not entirely accurate, it is ok to think of it as a group of scalars.

Now, for the mapping \(E\) to be called a pairing, it should satisfy 3 properties:

Bilinearity: What bi-linearity means is that for points:

\(P,Q \in G_{0} \text{ and } S,T\in G_{1}\), these two conditions hold true:

1. \(e(P+Q, S) = e(P,S) \cdot e(Q,S)\), and

2. \(e(P,S+T) = e(P,S) \cdot e(P,T)\)This can also be expressed as follows:

\(e(aP, bS) = (e(P,S)^a)^b= (e(P,S)^b)^a = e(P,abS) = e(abP,S)\)

Honestly, just look at this last line of equations.Non-degeneracy: (Sorry, I tried, but at the time of writing I just don't understand what this property means exactly. However, you don't need to focus too much on properties 2 and 3. Make sure you understand bi-linearity. Will update this part of the article when possible).

Efficiency: This just means that \(e\) should be "efficient enough" to compute. Computing these pairings efficiently is a complex task actually.

The main takeaway here is the bi-linearity formula.

if you understand that a pairing \(e\) is a mapping that takes elements from two groups \(G_{0} \text{ and } G_{1}\) to the scalar in the Target group \(G_{T}\), and it also satisfies the bi-linearity formula, basically that you can just move the coefficients into the exponents and also to the other side and the equality still holds then you're ready for the next part.

Pairings for verification

Let us go back to why we introduced pairings in the first place.

I have \(200G=A \text{ and } 275G=B\), and everyone knows the value of \(G\), now you can calculate \(C = A+B\), even though you don't have the secret values of 200 and 275.

On the other hand, since I have the secret value, I will first add 200 and 275 to get 475, and then I will just calculate \(475G\).

You can thus verify my calculation, that \(A+B=C\), even though you have none of the scalar coefficients.

Now let us apply this concept to multiplication.

For the same points, we know that there will be some restrictions in place when it comes to multiplication.

We can do \(A+B\), but we cannot do \(A \cdot B\), where \(\cdot \) represents multiplication.

Let \(A \cdot B = D\). You cannot calculate \(D\) since you don't know the secret values of 200 and 275.

But I do know the values of 200 and 275. So I can calculate the value of \(D\) like this:

\(A \cdot B = (200 \cdot 275)G = D\)

I now give you \(A,B,G, \text{ and }D\). But I DO NOT give you the scalar coefficients. So how do you verify that indeed performed the calculations correctly?

How do you verify that I did not cheat?

By using the mapping algorithm.

Note that \(e(A, B) = e(200G,275G) = e(G,(200 \cdot 275)G)= e(G,D)\)

Now you don't know about 200 and 275, but if in your mapping calculation,

\(e(A, B) = e(G,D)\), then you know for a fact that I did my work honestly.

Conclusion

I wrote these 2 articles after religiously going through the 3 cryptography videos posted by KoalateeCtrl.

You can find those videos on Youtube.

You should now have a basic understanding of how cryptography could work like in blockchain.

I will publish more articles on this blog about math and cryptography. Make sure to follow this blog if you want to tag along.

You can also hit me up on Twitter if you have any feedback.